Gross distortions in Malaysia’s voting system

Malaysiakini

Gross distortions in Malaysia's voting system

Ramesh Rajaratnam

8:23AM May 9, 2013

COMMENT The recently completed May 5 general election (GE13) revealed some interesting facts and figures based on the results as published by the Election Commission.

There have been, for a long time, much criticism of the ‘first past the post' (FPTP) election system we practise in Malaysia, because of what is inherent in this antiquated system.

The FPTP is one of the legacies of the British rule in Malaya and was based on giving all segments of the populace a voice in Parliament. Hence, constituency boundaries were drawn based on this segmental need for representation.

The original intention was noble indeed, that people in Sungai Buloh should have a voice in Parliament, just as those from Shah Alam, even though the Shah Alam constituency may have a population five times larger.

To prevent abuse and disproportional representation, certain limits were set when our founding fathers drew up the federal constitution. One important feature was that there should not be a population variance greater than 20 percent between the smallest and largest constituencies.

This safeguard was gradually eroded by successive ruling governments, since they enjoyed two-thirds majority Parliament to amend the country's laws, until this sanity check on societal representation was totally removed.

As a result of this, today we have 26,000 voters in Putrajaya, Igan (18,000) and Lubok Antu (19,000) commanding the same parliamentary voice as those in Kapar (144,000), Serdang (133,000) and Gombak (123,000).

This hardly seems fair when three small zones command an equal representation in Parliament, compared with their brethren who are at least five times larger, at least from the perspective of a majority rule.

Disproportionate representation

Criticism of such disproportionate representation led to some countries, such as New Zealand, Australia and Israel, modifying their electoral constituencies to be more representative and hence, the FPTP no longer applies in toto in these countries.

In a related example, besides throwing 90,000 tonnes of tea into the Atlantic Ocean, a new country was born some 237 years ago simply because its ‘rakyat' couldn't accept taxation without representation. One can draw similar parallels, if this inequitable scenario was to ensue here in Malaysia.

The greatest disservice of this FPTP system was shown clearly in Malaysia in GE13 when 915,560 voters in East Malaysia sent 48 BN candidates to our Parliament, or simply put, the average vote cost per BN lawmaker was 19,074.

Because of the severe skewering (aka gerrymandering) of the constituency delineations, it cost an average of 84,053 votes to get one Pakatan Rakyat MP in East Malaysia, or 4.4 times more expensive.

On the national average, it cost BN 39,381 votes per MP as opposed to Pakatan's 63,191 votes. Quite frankly, Pakatan had to work 60 percent harder than the BN had to.

On the national average, it cost BN 39,381 votes per MP as opposed to Pakatan's 63,191 votes. Quite frankly, Pakatan had to work 60 percent harder than the BN had to.

What this means is that unless the present delineation boundaries are redrawn to fix this severe misrepresentation of societal voice, any opposition will need about 60 percent of the national votes to be on par with BN come election time, forever.

Here, I dare opine that GE13 was largely won by BN by capitalising on the severely disproportional FPTP system, rather than on phantom voters, repeat voters and such. Several jumbo jets full of Bangladeshis, Burmese and Nepalese could not have caused the damage to Pakatan as done by this antiquated Westminster delineation system.

From a strategic point, there should have been more focus in the territories where the opposition could have got more "bang for its ringgit" (pun intended) because the voter distribution and pattern (based on past election results) would have been known upfront anyway.

Admittedly, getting Pakatan's voice to the people in the jungles of Borneo would have been a Herculean task, given the physical and political hurdles.

However, mathematically speaking, if Pakatan had won the same number of seats from the 915,560 voters and maintained the same results in the peninsula, it would be firmly in power now.

Perhaps that's the reason why the BN is believed to have chartered several flights to carry voters from the peninsula to Sabah and Sarawak. I'm inclined to believe that the BN knew, from day one, that this was how it would win GE13.

Some interesting facts

Based on the Election Commission website, let me highlight these other interesting facts from the FPTP vis-à-vis GE13:

1) BN received 46.2 percent of the popular votes in Peninsular Malaysia and 54 percent in East Malaysia, or a national average of 47.4 percent.

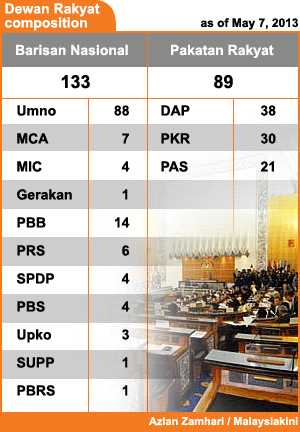

2) Based on this, BN was able to garner almost 51 percent of the parliamentary seats in the peninsula and 87.3 percent of those in Sabah and Sarawak, for a national average of 60 percent, or 133 seats.

3) Interestingly, 8.2 percent of the voters (in Sabah and Sarawak) gave BN 22 percent of the parliamentary seats, meaning 39.2 percent of the voters (in the peninsula) gave it the remaining 38 percent in Parliament.

4) Pakatan received 54 percent of the popular votes in Peninsular Malaysia and 35 percent in East Malaysia, for a national average of 51 percent.

5) Based on the above, Pakatan was only able to garner 49 percent of the parliamentary seats in the peninsula and 12.7 percent of that in Sabah and Sarawak, for a national average of 40 percent, or 89 seats.

6) It cost Pakatan 21 percent and 441 percent more votes per MP in the peninsula and East Malaysia respectively, to be on par with BN. On average nationally, Pakatan had to work 60 percent harder per MP than the BN.

6) It cost Pakatan 21 percent and 441 percent more votes per MP in the peninsula and East Malaysia respectively, to be on par with BN. On average nationally, Pakatan had to work 60 percent harder per MP than the BN.

7) Because they only formed 29.8 percent of the voters in GE13, contrary to the "Chinese tsunami" conspiracy theory, even if 100 percent of Chinese Malaysians (and for good measure, let's also throw in 100 percent of Indian Malaysians as well) voted for the opposition, there is no way Pakatan could have logically garnered the support of 5,623,984 Malaysians.

Conservatively adjusting for a 25 percent Chinese support for MCA and Gerakan (as was seen where there was a large Chinese voter base), at least three million voters therein were Malay/bumiputera.

This means, conservatively, 42 percent of the Malay/bumiputera electorate in Malaysia actually voted for Pakatan nationally. To put this into proper context, there was no such Chinese tsunami but instead, it was a Malay/bumiputera tsunami because 56 percent of the opposition's votes actually came from the Malays/bumiputera.

For Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak to have made this arithmetic blunder publicly was totally ill-advised and it has now caused needless uneasiness among the rakyat.

8) Finally, as explained earlier, 915,560 people, who are basically very removed from urban and national politicking, more or less sealed the fate of 11,054,577 voters or about 29 million people in Malaysia – thanks to the FPTP system.

Seriously and practically speaking, would anybody consider 3.2 percent (915,560) of Malaysians deciding the future of the country a fair run of democracy under the FPTP voting system?

Without a concerted effort from our MPs to make our country fairer by insisting on equitable representation in Parliament, it will indeed be very difficult for Najib to ask for national reconciliation when the very premise of his assertion was fundamentally flawed.

If you don't know what's broken, how can you fix it?

DATO RAMESH RAJARATNAM is a chartered accountant and a keen follower of Malaysian politics.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.